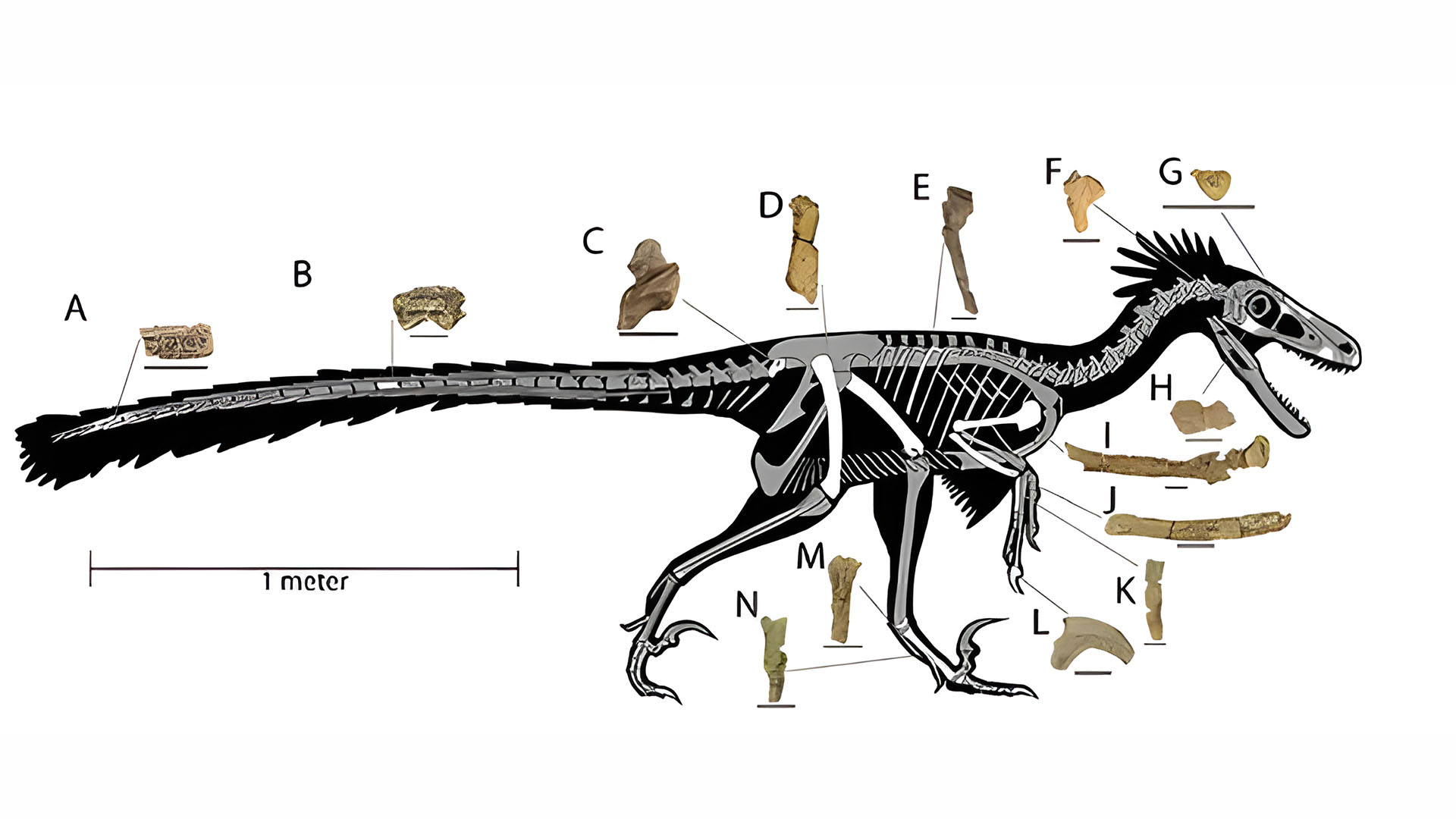

Chuck Norris probably kept one as a pet. [Picture used under Creative Commons license, from Jasinski et al. 2020, margins modified].

Paleontology Newsflash: Dineobellator hesperonotus

- First, an important caveat: pop culture gives all ‘raptors the ecological role of soulless killing machine. In reality, though, dromaeosaurs employed a wide variety of survival strategies. Microraptor could glide and enjoyed the diet of a housecat (minus the milk). Deinonychus may have depended on Tenontosaurus for food much like wolves depended on bison. Bambiraptor could pick things up with one hand, but Austroraptor couldn’t and on top of that had reduced arm length and specialized in eating fish. Giant Utahraptor sacrificed speed for strength, giant Dakotaraptor sacrificed strength for speed, and giant Achillobator had a weird leg and hip design whose function remains unclear (Strength? Speed? Hops? Who knows?). All in all, ‘raptors lived a pretty diverse set of lifestyles. So when it comes to figuring out how Dineobellator behaved, we can’t just say it acted like Velociraptor because it belonged to the family and grew to the same size. The bones we have tell us Dineobellator was its own beast.

- Starting with the head, several broken chunks survived as fossils, along with a single tooth. The skull bits don’t tell us much, but the tooth is small and sufficiently different from another ‘raptor found in the same formation, known as Saurornitholestes, that future studies could determine whether they shared the same environment. Features of the tooth, including small size and a slight saw edge with rounded denticles, resemble those of other theropods like Allosaurus that slashed or plucked at prey rather than crushing or tearing like Tyrannosaurus did. Functionally, its teeth fit the general ‘raptor profile and suggest it could hold struggling prey.

- Dineobellator’s arms give us the most information about the animal. It featured unusually large sites for muscle attachment, especially the delto-pectoral crest, with a resulting muscle arrangement that retained the arm’s general flexibility. This gave it agile yet powerful arms, especially suited for pulling things toward the chest. Coupled with extraordinarily large muscle attachment sites on its hand claws, this suggests Dineobellator ‘s survival strategy favored an incredibly strong grip, probably used in subduing prey.

- In addition, Dinebellator’s forearm shows bumps that may represent quill knobs. Some of its close relatives, like Velociraptor and Dakotaraptor, feature similar bumps, which could indicate the presence of feathers. When a bird puts feathers under unusual stress, the follicles sometimes anchor onto the bone itself via a ligament, forming quill knobs. Feathers might seem like a pretty counterintuitive thing to put on an arm designed for grappling, but maybe that’s what put them under stress. In any case, these knobs only hint at the presence of feathers, but they give us no information on their length, shape, patterning, or any other physical characteristics. Without that data, figuring out what ‘raptors did with those feathers that put them under such stress is a tricky proposition. The scientists who describe Dineobellator speculate: “It has been shown that coloration and patterns highly discernible within taxa may not have the same effect on prey. This implies that feathers can act as bright markers, species-recognition markers, and/or sexual display features without being visual signals that call attention of predators or prey. Modern raptorial birds show that color patterns can still be intricate and serve to both camouflage the predator and be part of the sexual selection process, and similar feather styles may have been present in dromaeosaurids.” In other words, ‘raptors like Dineobellator may have carried a sort of biological flag or insignia on their arms. Hopefully future fossils will allow us to test this idea.

- Back to its hand claws, they compare pretty impressively against other ‘raptors. Their muscle attachment area takes up 93% of the area needed to keep them attached to the rest of the skeleton. To illustrate, picture a bony lump coming off the bottom of your own finger that nearly matches the thickness of the finger itself, then attach muscles to it. That’s pretty powerful. Now compare that to other ‘raptors: Bambiraptor—55%, Deinonychus—55%, Microraptor—56%, Velociraptor—77%. As if that didn’t impress enough, Dineobellator’s foot claws (not even the sickle claw, which wasn’t recovered) display an incredible grip strength as well: Dineobellator—67%, Bambiraptor—17%, Deinonychus—36%, Velociraptor—20%. Even giant dromaeosaurs like Dakotaraptor and Utahraptor only reached 50% and 40% respectively. Whatever it was doing with these claws, it seems built to hold on for dear life. Its relatives seem tame by comparison, even if many of them hold the same reputation.

- The base of Dineobellator’s tail has a unique ball-and-socket design that combines strength with great mobility. Most dromaeosaurs exhibit greater flexibility at the base of the tail (and even some stiffness for the rest of its length) than other dinosaurs. A similar design also appears in long-tailed pterosaurs. Even though dromaeosaurs could not fly—the smallest ones could only glide—such a tail design probably made them more agile. They may have had a cat-like ability to shift their body orientation in the air, albeit using a completely different strategy than cats. Dineobellator seems to have taken that agility to an extreme.

- Finally, many of the few bones recovered show abnormal bone growth. Differences in the patterns of this pathological growth suggest it all comes from different injuries the animal sustained throughout its life. One injury on its hand claw, which shows no bone remodeling, hints that this animal died during a fight with another Dineobellator.

- What does all this mean? Putting all the evidence together into a portrait of the species, it’s easy to picture Dineobellator as a sort of dinosaurian rodeo cowboy from your worst nightmares. What might explain such a specialized grip, hand and foot, so well as seeing this beast jumping onto a larger dinosaur that would try to buck it off? What might motivate that bucking so much as a nasty beast ripping chunks out of the prey’s back? And that’s a worthwhile hypothesis to explore. With any luck, we’ll get fossils that will allow us to test this scenario. Until then, though, it’s best to consider this behavioral profile for Dineobellator as provisional at best. (Personally, though, my bet remains on this critter acting like a soulless killing machine, based purely on available evidence, of course.)

Jasinski, S.E., Sullivan, R.M. & Dodson, P. New Dromaeosaurid Dinosaur (Theropoda,

Dromaeosauridae) from New Mexico and Biodiversity of Dromaeosaurids at the end of the

Cretaceous. Sci Rep 10, 5105 (2020).

Torices, A., Wilkinson, R., Arbour, V. M., Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I., & Currie, P. J. (2018). Puncture-and-

pull biomechanics in the teeth of predatory coelurosaurian dinosaurs. Current Biology, 28(9), pull biomechanics in the teeth of predatory coelurosaurian dinosaurs. Current Biology, 28(9), 1467-1474.

Turner, A. H., Makovicky, P. J., & Norell, M. A. (2007). Feather quill knobs in the dinosaur

Velociraptor. Science, 317(5845), 1721-1721.